A Cold War Childhood

It seems like almost every generation has some terrible thing that scares the heck out of its children. In World War II American kids were afraid that Hitler’s Nazis would invade and turn them into slaves. Earthquakes have scared California kids for decades. They still practice stop, drop, and cover—getting under desks or in doorways to protect themselves from the world crashing down on their heads. Today’s children face the most frightening fear of all: crazy people bursting into their classroom and mowing them down with assault rifles. Active shooter drills might help save lives, but the anxiety they provoke must be having a scary effect.

As a baby boomer, my fear was nuclear war. In 1949 the Soviets stole our atomic bomb technology. By the ’50s and early ’60s as the Cold War escalated, the Soviet Union and America had hundreds, if not thousands, of bombers and missiles ready to completely wipe out each other. It was assumed that Russia would take out big cities, military bases, and strategic targets in the first phase of an attack. A bomb would vaporize the center of anything it hit. Pittsburgh and its steel mills was assumed to be an important target. The blast wouldn’t hurt us in Titusville, 100 miles away, but we still weren’t off the hook. Radioactive fallout can travel hundreds or even thousands of miles, depending on the winds. We were going to die slowly from radiation sickness, or more quickly at the hands of marauding bands of hungry people looking for food.

I wasn’t the only kid who was pretty sure that an attack, to be followed by a nuclear winter, was coming. I spent endless amounts of time worrying. In school, not paying attention to class, as usual, I would try to figure out our survival strategy.

Government publications instructed people on what to do in case of an emergency. Regular drills were held on the radio and TV to test the emergency broadcast system. “Drop and cover” was practiced in school. The top thing the government recommended was to build a fallout shelter. Dig a huge hole in the backyard, build a shelter, cover it up with a couple of feet of dirt, and you might be safe. Of course, you had to stock it with water, food, medicine, etc.

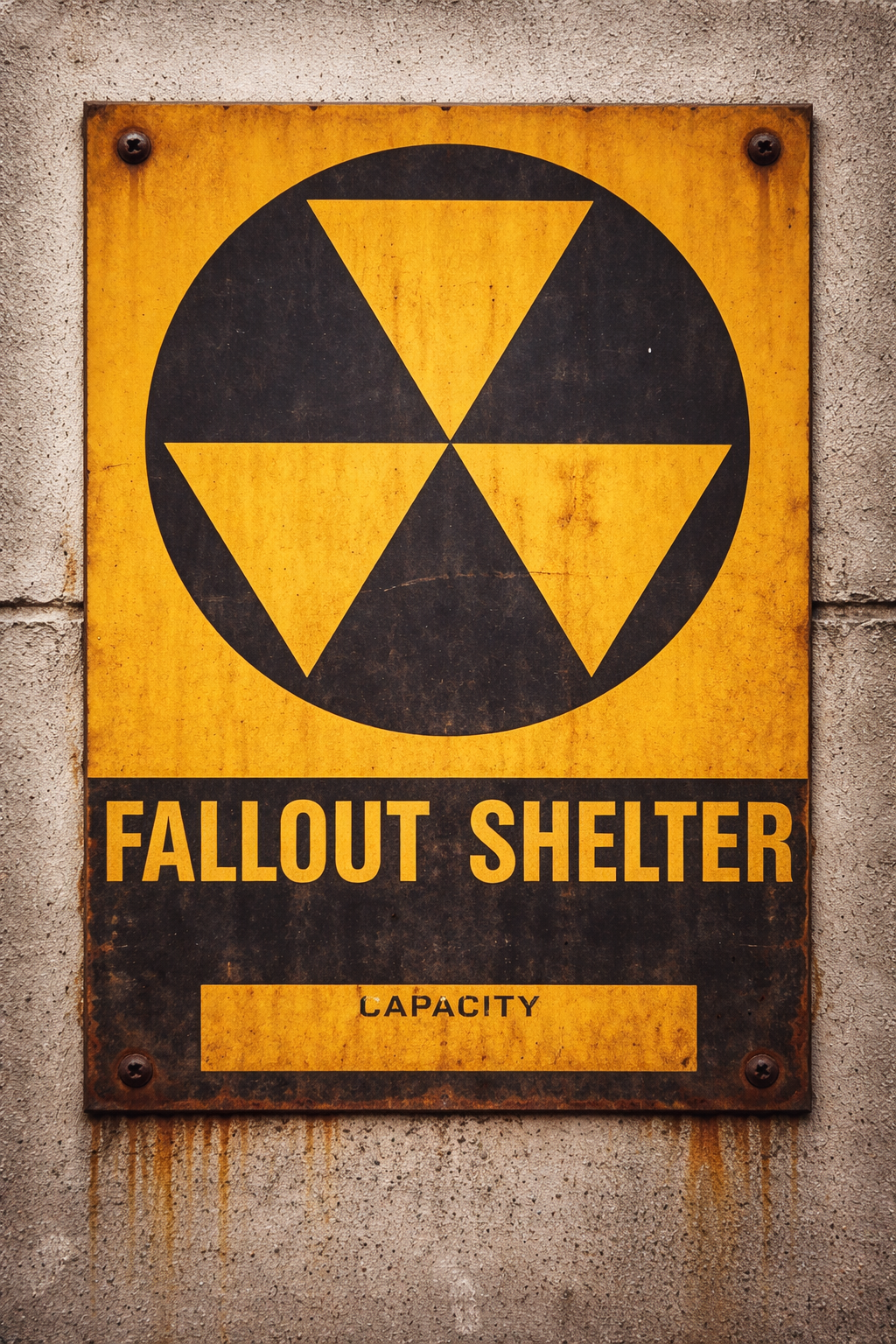

The government put up signs across the country to designate fallout shelters for people who didn’t have their own shelter.

Placed on thousands of buildings across America

Although some of their friends built fallout shelters, our parents either weren’t that frightened, or didn’t want to spend the money. The strategy I developed for an attack was to fill up our bathtubs with water. Then, I would cover the floor of the dining room with all the books in the house. Hopefully they would absorb the harmful radiation that was going to be raining down upon us in the basement below—our new home.

There were grim TV shows that depicted the apocalypse that was coming. One of them was “The Day Called X”, which aired on CBS in 1957. I remember it vividly, including its optimistic ending (we beat the hell out of them). It was scary.

There were several times in my childhood when some emergency caused the nuns to move us all to the school basement. One of the most memorable came during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. I can’t remember the exact point in that crisis that precipitated the basement move. It all started with the Russians building missile sites in Cuba. Ships carrying nuclear missiles were starting to arrive. Only 90 miles from the U.S.; we would have no time to react.

President Kennedy imposed a naval blockade and did some fast talking with Khrushchev. The ships turned back, averting the crisis. In exchange, we promised not to invade Cuba, and to remove our missiles in Turkey. I was relieved after feeling like we were in serious danger.

The Russians were definitely the bogeymen of my childhood. An attack never came, thank goodness. So, I would have been better off spending my time in class studying algebra and Latin.